- Home

- Alan Campbell

Scar Night; Book One of the Deepgate Codex Trilogy

Scar Night; Book One of the Deepgate Codex Trilogy Read online

SCAR NIGHT

Book One of the Deepgate Codex Trilogy

Alan Campbell

PROLOGUE

CHAINS SNARLED THE courtyard behind the derelict cannon foundry in Applecross: spears of chain radiating at every angle, secured into walls with rusted hooks and pins, and knitted together like a madwoman’s puzzle. In the centre, Barraby’s watchtower stood ensnared. Smoke unfurled from its ruined summit and blew west across the city under a million winter stars.

Huffing and gasping, Presbyter Scrimlock climbed through the chains. His lantern swung, knocked against links and welds and God knows what, threw shadows like lattices of cracks across the gleaming cobbles. When he looked up, he saw squares and triangles full of stars. His sandals slipped as though on melted glass. The chains, where he touched them, were wet. And when he finally reached the Spine Adept waiting by the watchtower door he saw why.

“Blood,” the Presbyter whispered, horrified. He rubbed feverishly at his cassock, but the gore would not shift.

The Spine Adept, skin stretched so tight over his muscles he seemed cadaverous, turned lifeless eyes on the priest. “From the dead,” he explained. “She ejects them from the tower. Will not suffer them there inside with her.” He tilted his head to one side.

Below the chains numerous Spine bodies lay in a shapeless mound, their leather armour glistening like venom.

“Ulcis have mercy,” Scrimlock said. “How many has she killed?”

“Eleven.”

Scrimlock drew a breath. The night tasted dank and rusty, like the air in a dungeon. “You’re making it worse,” he complained. “Can’t you see that? You’re feeding her fury.”

“We have injured her,” the Adept said. His expression remained unreadable, but he pressed a pale hand against the watchtower door brace, as if to reinforce it.

“What?” The Presbyter’s heart leapt. “You’ve injured her? That’s… how could you possibly…”

“She heals quickly.” The Adept looked up. “Now we must hurry.”

Scrimlock followed the man’s gaze, and for a moment wondered what he was looking at. Then he spotted them: silhouettes against the glittering night, lean figures scaling the chains, moving quickly and silently to the watchtower’s single window. More Spine than Scrimlock had ever seen together. There had to be fifty, sixty. How was it possible he’d failed to notice them before?

“Every single Adept answered the summons.”

“All of them?” Scrimlock hissed, lowering his voice. “Insanity! If she escapes…” He wrung his hands. The Church could not afford to lose so many of its assassins.

“She cannot escape. The window is too narrow for her wings; the roof is sealed, the door barricaded.”

Scrimlock glanced at the watchtower door. The iron brace looked solid enough to thwart an army. That still did not give him peace of mind. He looked for reassurance in the Adept’s eyes, but of course there was nothing there: only a profound emptiness the priest felt in his marrow.Could they have injured her? And what would be the cost to the Church? What revenge would she seek? God help him, this was too much.

“I will not sanction this,” he protested. He waved a hand at the heap of dead bodies, at the blood still leaking onto the cobbles. “Ulcis will not accept these opened corpses; every one of them is damned.”

“We have reinforcements.”

“And they will die too!” the Presbyter snapped. Yet he recognized a lack of conviction in his own voice.They’ve managed to hurt her . In a thousand years, no one had accomplished as much.

“Sacrifice is inevitable.”

“Sacrifice?Look at this blood! Look at it!” Scrimlock stepped back and lifted his cassock clear of the blood pooling around his ankles. “Hell will come for this blood, for these spilled souls. This courtyard is cursed! Evil will linger here for centuries. A hundred priests could not lift Iril’s shadow from these cobbles. Nothing can be saved here. Nothing .”

The Presbyter could not decide which horrified him more: the thought that their Lord Ulcis, the god of chains, would be denied the souls of so many of his Church’s best assassins, or that hell might be lurking somewhere close by. The Maze was said to open doors into this world to take the souls from spilled blood. Scrimlock searched the gloom around him frantically. Perhaps hell was already here? Were these souls passing even now through some shadowy portal into Iril’s endless corridors? If so, what might come through the other way? What might escape ?

“End this hunt now,” he said. “Let her escape. It’s too dangerous.”

“You wish her to survive?” the Adept said.

“No, I…” The Presbyter’s shoulders nudged against something, and he wheeled round in alarm. A chain. “I only wish to preserve the Spine,” he said, clutching his chest. “Pull your men back before it’s too late.”

A howl of laughter came from above.

“Reinforcements have reached the window,” the Adept said.

Scrimlock looked up. Smoke leaked from the jagged watchtower roof and spread like grease over the stars. The stone falcons and battlements had crumbled inwards, exactly as the sappers had promised, blocking access to the roof and thus blocking escape. The sulphurous smell of blackcake lingered. Halfway up the tower, the assassin nearest to them squeezed through the window.

A sword clashed loudly.

Scrimlock moistened dry lips. “She’s armed,” he said. “God help us, she’s defending herself with steel.”

“No,” the Adept replied. “Barraby’s stairwells and passages are narrow. Combat in such confines is treacherous. You merely heard a Spine blade strike stone. She remains unarmed.”

“I don’t understand.” The priest cast another glance over the corpses piled to one side. “There must be abandoned weapons in there. You cannot have removed them. Why does she not arm herself?”

A scream—followed by terrible laughter. Scrimlock felt nauseous. Both scream and laughter had seemed to issue from the same throat.

“We believe,” the assassin said, “she wishes to be defeated.”

“But that makes no sense. She—”

A noise from above distracted the Presbyter and he looked up in time to see a body being forced through the narrow watchtower window. Bones snapped, and then the body fell till it struck a chain. Arms and legs twisted around the massive links, and for a heartbeat it hung there, limp as a straw doll. Then it slipped free, bucked, and snagged on the chains further below, until it crumpled to the ground. Spans of iron tensed and shivered. Four more Spine had clustered around the outside of the tower window. They clung to bolts and hooks in the walls whereby the chains gripped stone. Others were climbing closer, from below. The assassin nearest to the window, a lean man, eased himself inside, after his sword.

He called down: “She’s cut, she’s—”

A wail, half torment, half rage, pierced Scrimlock’s heart. There were sounds of sobbing, like those of a frightened child, followed by a hellish cry. The assassin’s broken, bloodied body reappeared at the window and dropped a dozen feet before its neck snagged on one of the tower’s protruding bolts.

A third Spine peered in through the window. “She’s coming down.”

“What?” Presbyter Scrimlock retreated from the watchtower door. “We must get away from here. Now, quickly, we—”

“She cannot break through this door,” the Adept said. “Nothing can break through this.”

Scrimlock’s sandals slipped on blood-soaked cobbles. His lantern shook, dimmed, then brightened. Shadows clenched and flickered around him. Above them, Spine were climbing, one after another, through the window: three, six, eight of them.

“She will die now,” the Adept said flatly.

Boom.

Something struck the watchtower door from within, with the force of a battering ram. Dust shuddered free from its thick beams, and the Spine Adept pushed against the door brace.

“Get away,” Scrimlock said. “Leave her now, I beg you. This is her night.”

“Her last night,” the Adept said.

Boom.

The brace jumped. Wood cracked, splintered. The Adept pitched backwards, then lunged forward again and threw all of his weight against the door. Scrimlock looked around, searching for the best way to escape. “It won’t hold,” he gasped. “She’ll—”

Steel rang inside the tower: sharp, furious strikes, like an expert butcher hacking meat. The assassins had descended to the other side of the door. Then another scream. More rapid concussions as blades struck stone. Scrimlock pressed his fists over his ears, sank to his knees. His limbs were trembling. He began to pray.

“Lord Ulcis, end this, I beg you. Let your servants prevail.” Let this door hold. “Spare these souls from the Maze, spare us all, spare me, spare me.”

Silence.

“It’s over.” The Adept shifted his weight from the door brace.

Boom.

The watchtower door exploded outwards, its timbers shattered like rotten boards. The brace crashed to one side. The Adept was thrown clear, colliding with a chain, but Scrimlock was astonished to see the man’s sword was already out; he was already rising to his feet.

Then the Presbyter looked at the gaping hole where the watchtower door had been.

Something stood there, darker than the surrounding shadows.

“She’s here,” he hissed.

The angel stepped out into the lane, small a

nd lithe and dressed in ancient leathers mottled with mould. Her wings shimmered darkly, like smoke dragged behind her. Her face was a scrawl of scars: more scars than could have been caused by the current battle with the Spine, more scars than a thousand battles could have caused. Blood spattered her similarly scarred arms and hands, and her eyes were the colour of storm clouds. She wore flowers and ribbons in her lank, tangled hair. She had tried to make herself look pretty.

She was unarmed.

Scrimlock, still on his knees, said, “Please.”

One corner of the angel’s scarred lips twitched.

“Run,” she whispered.

The Presbyter scrambled to his feet and bolted. Fast as his leaden limbs could carry him, he stumbled and weaved though the chains. Spine were slipping soundlessly to the ground all around him, pale faces expressionless, swords white with starlight. They converged on the angel.

Scrimlock didn’t stay to witness the slaughter. Clear of the tangles of iron, he ran and ran; away from the crash of battle, away from the howls of pain and anguish; away from the unholy laughter. And away from the Spine, who never made a sound as they died.

2,000 YEARS LATER

1

DILL

TWILIGHT FOUND THE city of Deepgate slouched heavily in its chains. Townhouses and tenements relaxed into the tangled web of ironwork, nodded roofs and chimneys across gently creaking lanes. Chains tightened or stretched around cobbled streets and hanging gardens. Crumbling towers listed over glooming courtyards, acknowledging their mutual decay. Labyrinths of alleys sagged under expanding pools of shadow; all stitched with countless bridges and walkways, all swaying, groaning, creaking.

Mourning.

As the day faded, the city seemed to exhale. A breeze from the abyss sighed upwards through the sunken mass of stone and chain, spilled over Deepgate’s collar of rock, and whistled through rusted groynes half-buried in sand. Dust-devils rose in the Deadsands beyond, dancing wildly under the darkening sky, before dissolving to nothing.

Lamplighters were moving through the streets below, turning the city into a bowl of stars. Lanterns on long poles waved and dipped. Brands flared. Gas lamps brightened. From the district known as the League of Rope, right under the abyss rim, and down through the Workers’ Warrens to Lilley and the lanes of Bridgeview, lights winked on among thickets of chain. Chains meshed the streets, wrapped around houses or punctured them, linking, connecting, weaving cradles to hold the homes where the faithful waited to die.

Now all across the city, sounds heralded the approach of night: shutters drawn, bolted with a clunk and snap; doors locked, buttressed; padlocks clicked shut. Grates slammed down over chimney tops, booming distantly in all quarters. Then silence. Soon only the echoes of the lamplighters’ footsteps could be heard, hurried now, as they retreated into the shadowy lanes around the temple.

The Church of Ulcis rose unchallenged from the heart of Deepgate, black as a rip in the blood-red sky. Stained glass blazed in its walls. Rooks wheeled around its spires and pinnacles. Gargoyles crowded dizzy perches among flying buttresses, balconies, and crenellated crowns. Legions of the stone-winged beasts stared out beyond the city, facing towards the Deadsands: sneering, grinning, furious.

Lost amidst these heights, a smaller, stunted spire rose from the shadows. Ivy sheathed its walls, smothered one side of a balcony circling the very top. Only a peaked slate hat broke completely free of the vegetation, skewed but shining in the waning light. A rusted weathervane creaked round and round, as if not knowing quite where to point.

Clinging to this weathervane was a boy.

He hugged the iron with thin white arms. Tufts of hair shivered behind his ears. His nightshirt fluttered and flapped like a tattered flag. For a long time he held on, all elbows and knees, turning regularly with the weathervane, studying the surrounding spires with quick, nervous eyes. His toes were cold and he was filthy.

But Dill was happy.

Warily, he stood upright. The north-south crossbar tilted under his bare feet, moaned in protest. Rust crumbled, murmured down the slates below. A flock of rooks broke around him, screaming, then uncoiled skywards to scatter among the gargoyles and jewelled glass. Dill watched them go, and grinned from one pink ear to the other.

Alone.

He took a deep, hungry breath, and another, and then unfurled his wings and let the air gather under his feathers. Muscles in his back tightened. Blood rushed through his veins, reached into his outstretched wings. The wind buoyed him, tugged him playfully, daring him to let go. He leaned out and threw back his head, eyes bright. The weathervane spun him like a carousel. An updraught swelled under him. He flexed his wings, straightened them, and pulled down on them. His feet lifted and he laughed.

Someone hissed.

A hooded figure hunched at a window, yellow lantern raised.

Dill scrambled to clutch the weathervane to his heaving chest. He folded his wings tight and dropped to a crouch, heart thumping.

The figure hovered for a while, the shadow of its cowl reaching like a talon over the temple’s steeply canted roofs. Then the figure lowered the lantern and moved away.

Dill watched the priest’s shadow flit over the glass before the same window went dark. A hundred heartbeats passed while he clung there shivering. How long had the priest been there? What had he seen? Had he just then happened to pass by, or had he been hiding there in the room, waiting, watching, spying ?

And would he inform on Dill?

The tracery of scars on Dill’s back suggested he certainly might.

I didn’t fly. I wasn’t going to fly. He’d only unfurled his wings to feel the wind. That was all. That wasn’t forbidden.

Still shaking, Dill climbed down from the weathervane and squatted where the moss-covered cone capped the surrounding slates. At once there seemed to be watchers hovering at every window, hooded faces scrutinizing him from all around, unseen lips whispering lies that would find their way back to the Presbyter himself. Dill felt blood rise in his cheeks. He tore free a scrap of moss and feigned interest in it, scrunching it in his palm without feeling it, examining it without seeing it. As he let it go, the wind snatched it and carried it out over Deepgate.

It was said that once, you could have stood on the lip of the abyss and peered into the darkness below the city with nothing but the foundation chains between you and the fathomless depths. A sightglass, perhaps, might have offered views of the ghosts far below—but not now. The great chains were still down there, somewhere, hidden beneath the city that a hundred generations of pilgrims had built. But time had seen cross-chains, cables, ropes, girders, struts, and beams grow like roots through those ancient links. Buildings had been raised or hung, bridges and walkways suspended, until Deepgate had smothered its own foundations.

Dill lifted one calloused foot and thumped it down. A slate shattered under his heel. He picked up a fist-sized chunk of it and swung his arm to throw it at the window. But he stopped in time. The windows were old, maybe even as old as the temple and the foundation chains. As old as the roof tile he’d just broken, he thought miserably. Instead he hurled the slate into the sunset and listened hard to hear whether it hit anything before falling into the abyss beneath the city.

Glass shattered in the distance.

He flopped back, not caring if he crushed his feathers, and gazed past the twinkling streets to where the Deadsands stretched like rumpled silk to the horizon. Purple thunderheads towered in the west, limned in gold. To the east, the Dawn Pipes snaked into the desert, and there a ripple of silver in the sky caught his attention. He sat up.

An airship was purging its ribs for descent, venting hot air from the fabric strips around the liftgas envelope. Turning as it descended, it lumbered toward the Deepgate shipyards, abandoning the caravan it had escorted in from the river towns. The caravan threaded its way between water and waste pipes, the camels trailing plumes of sand. Behind the merchants, a line of pilgrims shuffled in their shackles between two ranks of mounted missionary guards.

“See you tomorrow,” Dill murmured, but he didn’t really imagine he would. It would be days before the pilgrims died.

Darkness was creeping into the sky now, pierced by the first evening stars, and so he slid the rest of the way down the roof, hitting the gutter with a thump and a tussle of feathers. A rotting trellis, overgrown with ivy, formed a rustling, snapping ladder back down to his balcony. When his feet finally found solid stone, he was shaking more than ever.

Lye Street

Lye Street Scar Night; Book One of the Deepgate Codex Trilogy

Scar Night; Book One of the Deepgate Codex Trilogy Art of Hunting

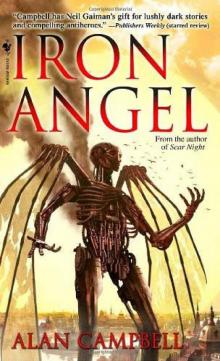

Art of Hunting Iron Angel

Iron Angel Gravedigger 01 - Sea Of Ghosts

Gravedigger 01 - Sea Of Ghosts Scar Night

Scar Night The Art of Hunting

The Art of Hunting God of Clocks

God of Clocks Iron Angel dc-2

Iron Angel dc-2